In this issue:

For the past 70 years, since Japan launched its first pelagic whaling fleet, the government has given free rein to Japanese whaling companies to plunder the world’s whales. From the beginning, Japan has refused to adopt international agreements or actively allowed its whalers to evade treaty obligations that it did sign.

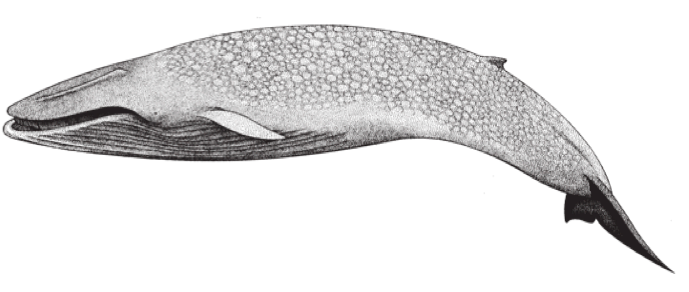

Tens of thousands of endangered whales, “protected” under international treaty, were harpooned by Japanese whalers over seven decades, often by Japanese owned whaling fleets based in outlaw nations, and even by pirate whaling ships roaming the high seas. The last of the blue, humpback and right whales were hunted to “commercial extinction” by these ruthless whalers.

The Japanese Imperial Army directed the whaling massacre in the 1930s. Professor George Small wrote in The Blue Whale: “It is evident…that the Japanese government prior to 1940 had no desire to impose any restraints on its pelagic whaling fleets. To have imposed any would have resulted in decreased production at a time when Japanese military aggression was placing severe demands on all sectors of the economy.

The pelagic whalers of Japan were thus free to kill any whale regardless of species or size at any time.

“During those years, several international agreements, designed to prevent overexploitation of stocks of whales, were reached under the aegis of the League of Nations. The agreements included the standard prohibitions such as the killing of nearly extinct Right whales, suckling calves of any species, and females accompanied by a calf.

“Japan refused to sign or abide by any of the agreements. Moreover, Japan refused to participate in the negotiations leading to the agreements even when for her benefit the North Pacific, her oldest whaling areas, was specifically excluded.”

After World War 11, the Japanese government continued to give its whalers carte blanche. Although Japan reluctantly joined the International Whaling Commission in 1951, four years after its creation, it immediately handed policymaking to the Japan Whaling Association, an organization of the Whaling companies. The Japanese commissioner to the IWC until 1965 was the chairman of the JWA.

From 1951 to 1964, the Japanese commissioner, acting on the order of Japan’s giant whaling companies (Nippon Suisan, Taiyo and Kyokuyo), blocked all attempts at the IWC to halt the destruction of the blue and humpback whales. Even Norway, which created the modern whaling industry and led the assault on the Antarctic seas, was appalled by Japan’s intransigence and greed.

Japan only agreed to an IWC ban on hunting blue whales after its seven fleets, deploying more than 100 catcher boats, could not find a single blue whale in 1964. However, the whalers knew that a few remnant herds of this greatest of all animals survived in the sheltering fjords of southern Chile.

So while the Japanese government and whaling industry piously proclaimed their adherence to the blue whaling ban, the government deviously licensed its whalers to set up shore stations in Chile, which was not a member of the IWC. For four years between 1964 and 1968, the Japanese whalers killed 690 blue whales in Chilean waters, often pursuing mothers and calves into the deepest reaches of the fjords, where the still waters were stained with blood.

The rapacious Japanese whalers in Chile didn’t limit their hunt to just one endangered species; they also knocked off 13 humpback and three right whales. Moreover, they killed over 1,600 fin and sei whales, and more than 1,500 sperm whales. All of the meat and oil was shipped back to Japan. The government conveniently looked the other way.

Perhaps the most egregious whaling crimes were practiced by Japan’s Taiyo Fishery Co. It got into pirate whaling in 1968 in a joint venture with Norwegian whaling interests. A former Dutch catcher boat, the AM No. 4, was converted to a combination factory ship/ catcher boat by adding a huge freezer compartment and a stern slipway for hauling whales aboard for slaughter.

Renamed the Sierra, the pirate whaling ship roamed the North and South Atlantic for a dozen years, flying flags of convenience such as Bahamas, Somalia and Cyprus.

It killed thousands of whales outside IWC regulation, many of them “protected” blue, humpback and right whales. The meat and oil was shipped from various Atlantic ports to Japan on Taiyo reefers. The Sierra’s deadly rampage only stopped in July 1979 when it was put out of action by the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society ship, which rammed it outside the port of Oporto, Portugal. Seven months later, after undergoing repairs, the Sierra was mysteriously sunk in Lisbon harbor by limpet mines attached to its hull by persons unknown.

A sister pirate whaler of the Sierra, the Tonna, met an even more improbable fate. Because the Sierra had a narrow stern slipway, its owners had obtained a larger ship that could handle the huge fin whales found in the North Atlantic. A former Japanese stern trawler, the Shunyo Maru, was remodeled as a factory/catcher ship at the Hayashikane Shipbuilding yard in Japan. Hayashikane was a major subsidiary of Taiyo. The ship originally built there in 1966.

Renamed the Tonna and flying the flag of the Netherlands Antilles, Taiyo’s new pirate ship made an initial foray in April 1978 off the coast of West Africa, where it served as the factory ship for the Sierra’s deadly harpoons. In just 42 days, 102 sei whales were killed and the Tonna packed up 432 tons of frozen meat. The two ships the sailed north to Las Palmas in the Canary Islands to offload and resupply. There a massive new Norwegian harpoon gun was fitted on the bow of the Tonna.

While the Sierra remained in the port for repairs, the Tonna set off in search of fin whales west of Spain and Portugal. In less than a month, 38 of the giant whales – second only to blue whalers in size – were harpooned and butchered on the broad rear deck of the ship. By 22 July, the freezer compartments were jammed with 450 tons of meat; the Tonna rode low in the water as it turned south toward the Canary Islands.

The captain of the Tonna, a veteran Norwegian whaler named Kristof Vesterheim, was a greedy man. He and his officers were being paid a standard bonus of $2.50 for every ton of meat. When they spotted a huge fin whale dead ahead, they decided to make some extra, easy money.

The whale was harpooned and dragged to the rear of the ship, where giant winches slowly pulled the 66-foot carcass, weighing probably 70 tons, up the slipway. The sea had been calm that day 200 miles off the coast of Portugal. But an afternoon squall blew out of the west, rocking the ship.

As wind and wave buffeted the Tonna, the glistening dead whale slid to the port side of the deck, tilting it sharply. The convereted fishing vessel was unable to right itself. Waves washed onto the deck and into the open portholes and hatches. Saltwater cascaded into the engine room. The electrical control panel shorted out in a blaze of sparks, sending acrid smoke billowing through the passageway.

The Tonna’s crew desperately tried to release the whale that was crippling the ship. But the electric winches were frozen, and the thick steel cables that had dragged the carcass on board were too thick to cut through quickly, Captain Vesterheim shouted orders to cut up the carcass and throw it overboard. The three Japanese flensers began madly hacking at the bulk.

In a scene of supreme irony, the Tonna wallowed helplessly like a harpooned whale.

The waves inexorably swamped the pirate whaler. At 7:40 p.m., the Tonna’s battery-operated emergency radio sent out a Mayday distress signal. The crew of 42, made up mostly of South Africans, scrambled into three life rafts.

But in a scene straight out of Herman Melville, Captain Vesterheim, decided to go down with his ship. Perhaps humiliated by his plight, he waved to the crew from the bridge as the Tonna sunk stern-first into the ocean depths, tugged down and down by another Moby Dick.

All of the crewmen were rescued unharmed later that night by a passing Greek freighter. Interviewed by authorities in Madeira, where they were dropped off, they all said they had been whaling “for the Japanese.” The three expert Japanese flensers, Isamu Shinkawa, Tatsuhide Saito and Masakichi Shibata, had formerly worked on Taiyo whaling ships.

Taiyo operated many more pirate whaling ships in the 1970s and 1980s, including the Cape Fisher, Susan, Teresa, Paulmy Star No. 3, and the Sea Bird. All flew flags of convenience and were based in non-IWC countries. Ownership was hidden behind dummy companies in offshore havens. All had Japanese crewmen in key positions. All of the whale meat was shipped to Taiyo in Japan.

The Taiyo Fishery Co. changed its name to Maruha a few years ago. Notorious even within Japanese industry, it probably did so in an attempt to help cover up its crimes against the whales.

Like other criminal acts of the Japanese Imperial Army in the 1930’s and 1940’s, the Japanese government is suppressing the fact that its pelagic (deep sea) whaling industry was created by the army for the sole purpose of financing the invasion of China and the conquest of the rest of East Asia.

Japan’s Manchurian Army, established in 1931 after the Japanese invasion of the northern Chinese province of Manchuria, became an economic giant by seizing the industries and resources of the vast region. In 1934 it purchased Japan’s first whaling fleet from Norway. By 1940, Japan’s six whaling fleets were larger than the combined fleets of all of the other nations in the world.

The driving force behind the Manchurian Army’s empire – and its rapacious whaling industry – were the warmongering General Hideki Tojo, who went on to become prime minister and launch the attack on Pearl Harbor, and a brilliant, ruthless, government bureaucrat, Nobusuke Kishi, who ran the financial side of the empire. Kishi signed the declaration of war in 1941.

Both Kishi and Tojo would be indicted as Class A war criminals after World War 11. Tojo was executed for his role as wartime dictator, but Kishi, charged with looting Manchuria and China, stealing private assets and enslavement of thousands of civilians to work in mines and factories, was released to help build an anti-communist movement in Japan. He served as prime minister from 1957 to 1960, a period the government pumped millions of dollars into Japan’s post-war whaling industry.

Nobusuke Kishi was also the grandfather of Japan’s current prime minister, Shinzo Abe.

From 1934 to 1942, tens of thousands of blue, fin, sei, humpback and right whales were ruthlessly slaughtered by the Japanese fleets in the Antarctic waters and the Pacific for the edible oil, which was sold in Europe for hard currency. All of the whale meat was thrown overboard because Japanese farmers, alarmed at the threat of their meat industry, pushed through a ban on whale meat imports.

The funds from the whaling massacre were used to purchase German and British arms, machine tools and other war material for the expansion of the Japanese empire.

“All of the pelagic fleets sent to the Antarctic were owned and operated by Nippon Suisan Kabushiki Kaisha Company, the main shareholder of which was the Manchurian Heavy Industries Corporation,” according to Prof. George Small in his award-winning history of the modern whaling industry, The Blue Whale. “This corporation was the principal economic and industrial arm of the Japanese army in Manchuria. The objective of the Nippon Suisan Company, as stated in the 1941 Mainichi Yearbook, was the acquisition of foreign currency and food supplies for the Japanese armed forces.”

In 1937, when Japan began to ally itself with Nazi Germany, most of Japan’s whale oil production was being sold to the German government, according to The History of Modern Whaling, produced by Norwegian Whaling Association.

After just three years in business, Japan accounted for more than 11 percent of the pelagic whaling. “Foreign whalers were seized with panic at Japan’s rapid progress: that the whale oil should have ended up in Germany was part and parcel of the extensive trade connections between the two countries, ushering in the military-political alliance of the Tokyo-Berlin Axis,” commented the Norwegian history.

In 1940, after war had broken out in Europe and shipping to Germany was too dangerous, thousands of tons of whale oil were stockpiled in Manchuria; efforts were made to ship some of it by rail to Germany through the Soviet Union. During the 1940-41 Antarctic whaling season, Japan’s six fleets deployed 51 catcher boats. They produced 622,413 barrels of whale oil. “In that season, Japan actually accounted for 59 percent of the pelagic Antarctic production,” states the Norwegian book.

Taking advantage of an expired ban on hunting humpback whales, the Japanese Antarctic fleets in 1941 harpooned 2,394 of the endangered species -- the same humpback stock that Japan until recently was planning to target in its “research” whaling scheme.

Under orders from the Manchuria Army, Nippon Suisan openly defied attempts to regulate the whaling industry in the 1930s. “During those years several international agreements, designed to prevent overexploitation of stocks of whales, were reached under the aegis of the League of Nations,” Dr. Small wrote. “The agreements included standard prohibitions such as the killing of the nearly extinct Right whales, suckling calves of all species, and females accompanied by a calf. Japan refused to sign or abide by any of the agreements even when for her benefit the North Pacific, her oldest whaling area, was specifically excluded. The reason for the refusal to adopt even rudimentary conservation practices was the urgent demand placed on the Japanese economy by the country’s war in Manchuria and China.”

Under the direction of Tojo and Kishi, the Manchurian Army -- called the Kwantung Army in Japan -- plundered not just the whales. Gold, artworks and other valuables were looted from Manchuria, and resources such as iron, coal and timber were stripped for shipment to Japan. The most ardent Japanese imperialists seized control of Manchuria’s riches to finance the conquest of all Asia.

“Real power in Manchuria was in the hands of the Kwantung Army and its underworld allies, overseen by General Tojo Hideki, head of the secret police,” reported Sterling Seagrave in his remarkable history of Japan’s royal family, The Yamato Dynasty. “Its economy was managed top to bottom by the newly formed Nissan Zaibatsu. The Kwantung Army became financially independent of Tokyo, able to act without budgetary restraint, peer review or government interference. Tojo became its chief of staff, on his way to becoming prime minister of Japan.”

“Such extraordinary success stimulated the Kwantung Army’s appetite to seize more territory. China was certainly more tempting than Siberia,” Seagrave explained. On 7 July 1937, the Kwantung Army set off a phony incident at the Marco Polo Bridge outside Peking. “An unidentified man shot at Japanese soldiers, allowing them to open fire on the Chinese defenders. The incident quickly escalated to full invasion and a China War that bogged down nearly a million Japanese troops for eight years.”

The Japanese Imperial Army pillaged and plundered as it moved through China, with the December 1937 Rape of Nanking, the capital of the Chinese Nationalist government, reflecting the army’s Three Alls Policy: “Burn All, Kill All, Seize All.” More than 250,000 non-combatants were brutally murdered in Nanking, and much of the undefended city was torched.

The whales, sadly, have suffered a “Three Alls” persecution at the hands of Japan since 1934.